How Yoga Works – a Scientific Look

How Yoga Works – a Scientific Look

by Chandrika (Cordula Interthal)

Yoga practice has many health benefits— these are the traditional yoga teachings. In recent years the scientific community has caught up to this fact with an increase in scientific research on yoga. In this article we will talk about how to understand scientific studies and the most researched topic: yoga and stress.

Yoga—A Spiritual Path

In light of the growing awareness of the health benefits of yoga and the creation of new fields like yoga therapy we should keep in mind that yoga is a spiritual path and its health benefits are ‘merely’ a step on the path to the highest goal.

This body is the moving temple of God. It should be kept healthy and strong. It is a vessel to take you to the other shore of fearlessness and immortality. ––Swami Sivananda

Yoga is a lifestyle and covers all aspects of life. Swami Vishnudevananda summarised this in the five points of yoga: asanas, pranayama, relaxation, proper diet, positive thinking and meditation. Most yoga studies look at the first three points: asanas, pranayama and relaxation. Although there is a wide variety of yoga styles in the scientific literature, most studies define asanas as postures that are held with a meditative component and relaxation elements.

Yoga is a lifestyle and covers all aspects of life. Swami Vishnudevananda summarised this in the five points of yoga: asanas, pranayama, relaxation, proper diet, positive thinking and meditation. Most yoga studies look at the first three points: asanas, pranayama and relaxation. Although there is a wide variety of yoga styles in the scientific literature, most studies define asanas as postures that are held with a meditative component and relaxation elements.

With regard to asanas, most of us may have heard that sarvangasana is good for the thyroid—this is traditional yogic knowledge. While the yoga masters and the traditional scriptures detail the benefits of specific asanas, scientific research looks into the benefits of holistic yoga practice, for example a sixty-minute yoga class daily for twelve weeks. This approach makes research easier and it also more accurately reflects the reality of our yoga practice in daily life.

Yogic and Scientific Thinking

If you practise yoga regularly you have already had the experience of its health benefits (remember—wellbeing is an important part of health). The Western mind may find it difficult to accept the yogic explanation of how yoga works (three bodies, five sheaths).

Scientific research may provide the last piece of the puzzle that we need to fully accept that yoga has many benefits and to be inspired to practise. Most scientific studies cannot and do not provide definite proof; they express this in phrases like ‘there is evidence…’.

Unfortunately, in our desire for getting yes or no answers, we are oftentimes tempted to simplify and take scientific findings as definite truth. With yoga studies it is especially important to be aware of this, because most studies on yoga lack the quality to give conclusive scientific proof of its benefits. Here are some tips to help you interpret scientific studies correctly:

1) A good study uses as many test subjects as possible and tests them as long as possible. Good questions to ask are: How many people were tested? How often and how long did they practise yoga?

2) Results from prospective studies are more significant than from retrospective studies. In a prospective study the test is done first before the data is collected. For example having a group of people practise yoga for twelve weeks and then measuring blood pressure afterwards. A retrospective study (case study) uses information from the past. For example comparing blood pressure in people that have practised yoga regularly for the last year against those who have never practised yoga.

3) The more studies that are done on the same topic with the same results, the more significant these results become. For example ten different studies showing that yoga lowers blood pressure is better proof than one study (reproducibility).

4) It is important to read the conclusion of the study carefully. ‘We couldn’t find any evidence for the effectiveness of yoga on lowering blood pressure’ can mean that the question remains unanswered because the study lacked the necessary quality.

‘We found evidence for the association between yoga and lower blood pressure’ is not yet definite proof; it means the two may be linked but it may not necessarily mean that yoga causes lower blood pressure and may mean further research is warranted.

Yoga and Stress

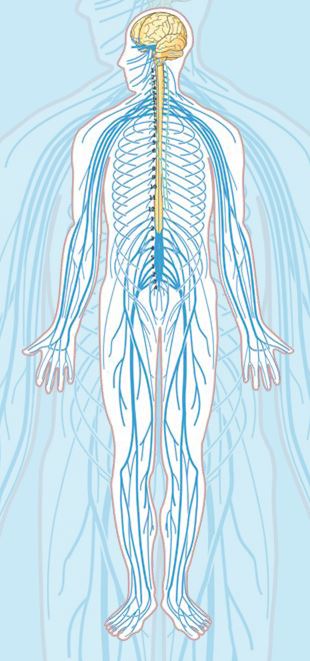

One of the best examples of scientific research on yoga is on its beneficial effects on stress, because there is so much data on it. Before we talk about stress we have to understand health and wellbeing, which is the constant change between two opposing systems in our body—the stress response and the resting state of relaxation. These two systems exist in a natural state of balance and regulate the subconscious functions of our body. They are linked in such a way that if one is activated, the other is down-regulated and vice versa.

It is just as the yoga masters teach us, a healthy life is a balanced life. Relaxation is the normal resting state of our body in which the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), the rest and repair system, is active. It is responsible for maintaining life including the impulse to breathe. If we need to become active the stress response, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS, fight or flight system), is turned on. It mobilises energy reserves, activates the cardiovascular system (this also involves the release of epinephrine into the blood) and increases muscle tone.

The SNS works closely together with the HPA system (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal system) which produces cortisol and is part of the hormone system. Both systems form one functional unit: the SNS/ HPA system. The main regulator of both systems is the hypothalamus, a small region in the brain.

Stress – Knocked Off Balance

Negative stress is a product of our modern way of life: the excessive and overly-long activation of the SNS/HPA system at the expense of the PNS. Our body has been knocked off balance and this can lead to fatigue, pain and disease. In this situation a vicious cycle unfolds. Repeated activation of the stress response makes the brain more receptive to stressful stimuli and quicker to activate the SNS/HPA system. At the same time the natural off-switch of the HPA axis stops working.

Under normal circumstances the HPA axis turns itself off once cortisol levels are high enough. Excessively elevated levels of cortisol override this mechanism resulting in a continuous, unfettered production of cortisol. We are all familiar with this situation. If you experience a large amount of stress y o u find it hard to relax, even after the stress is over. Your brain is still on alert, the SNS/HPA system is continuously active, and the PNS is suppressed.

Research on Yoga and Stress

The following is a summary of the many scientific findings on the topic:

Yoga turns OFF the stress response

In the brain, yoga inhibits the two areas of the hypothalamus which activate the stress response:—the areas responsible for activating the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the HPA axis. This stops the vicious cycle of continuous activation of both systems. In the body this effect can be seen in both the nervous system and the hormone system.

Dialling down of the SNS results in lower blood pressure, a slower heart beat and less catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) in the blood and urine. Inhibition of the HPA axis leads to lower blood cortisol levels.

Yoga turns ON the relaxation response

PNS activation can be measured by a more flexible heartbeat (increased heart rate variability) and greater sensitivity of baroreceptors, the internal blood pressure sensors. These additional findings also show that yoga reduces stress: yoga reduces blood sugar levels, inflammation markers, other hormones, pain medication use, and risk factors for heart disease.

Pranayama

Interestingly, breathing exercises alone also have a relaxing, stress-reducing effect. A slow breath with a long exhalation is a proven method of lowering blood pressure. It almost goes without saying then, that alternate nostril breathing also has been found to lower blood pressure.

Alternate nostril breathing is another very nice example of restoring the balance between the SNS and the PNS. Studies have found that unilateral right nostril breathing activates the SNS, while unilateral left nostril breathing activates the PNS and alternate nostril breathing activates the PNS.

Meditation

Studies have shown that meditation reduces the activity of the SNS and increases the activity of the PNS. This effect was strongest in higher states of meditation.

Positive Thinking

Positive psychology researchers have found that cultivating positive thoughts and emotions activates the PNS. In turn, the more relaxed an individual is to start out with, the more positivity he or she develops, showing nicely how the aspects of a holistic yoga practice boost one another.

Conclusion

Asanas, pranayama, positive thinking and meditation activate the relaxation system and take us out of the constant activation of the stress system. They restore balance and allow for constant harmonic change between both systems. In other words: they induce health and wellbeing.

Some interesting links

Yoga and Stress

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2156587217715927

https://altmedrev.com/blog/resource/the-effects-of-yoga-on-anxiety-and-stress/

www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/yoga-for-anxiety-and-depression

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=yoga+stress+review

General health benefits of yoga

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3193654/

www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2012/165410/

www.iayt.org/?page=HealthBenefitsofYoga

Chandrika is a gynaecologist and Sivananda Yoga teacher in Munich and at the Sivananda Retreat House in Austria. [email protected]